Today TECHknitting has a new use for an electrical appliance you probably already own: your steam iron. A stem iron is a mighty weapon against curling and flipping, so part of this post takes a detour into WHY bands want to flip in the first place. But before we plunge into all that, a brief look at the iron itself.

Steam irons, 101

Steam is vapor from boiled water. In order to make steam, your iron boils water inside a little chamber. Water contains minerals. Sometimes, the mineral load of the water is high enough to cause problems. If you always use the same pot or kettle to boil water, you already know whether boiling your water leaves behind mineral deposits. If your kettle stays clean regardless of how much water you boil in it, you have no worries. But if your kettle is mineral-encrusted, then so will the inside of your iron be.

A new iron will not give you trouble, even if you put in high-mineral-content water. This is because when water turns to steam, it leaves behind its mineral load. But as the inside of the iron's heating chamber becomes coated with minerals, the steam channels get clogged, and the iron starts spitting bits and flakes. Where I live, the water is hard from dissolved limestone, and tap water in a steam iron leads to whitish powder spraying out with the steam. In other areas, more staining minerals might be in tap water: iron (the metal) dissolved in water would cause your iron (the appliance) to stain your clothing in gray or brown splotches.

Therefore, if you have an new steam iron, keep it new by topping it up only with distilled water--a gallon from the supermarket will last a LONG time in most households. If struck with a sudden yen to start steam ironing, boiled COOLED water is a near substitute. Boil the water, let it cool in the pot, and pour the cooled water off, leaving the minerals behind. DO NOT USE BOILING WATER--first, you will hurt yourself, second, you might wreck the plastic parts of the iron, and third, the water does not shed the minerals until it cools.

If your iron is old, you should also use distilled (or boiled, cooled) water. Fill the iron with fresh water and steam-iron some old towels on the highest heat setting and the highest steam setting. Run at least three or four refills of water through the iron (this won't take that long--steam irons have tiny reservoirs). This will get the worst of the minerals out. If the iron seems to be getting clean, you might trust it on your woollies, but if you have any doubt, prudence dictates a pressing cloth or a flour-sack kitchen towel between the iron and the woollies. (This is also a good idea to prevent scorching, more, below.)

Another problem with irons is gooey sticky stuff melted onto the sole plates. This arises from ironing plastic-y dust onto clothes, or ironing synthetics on a high setting: they melt. The cure is

iron cleaner. The old fashioned remedy was to turn the iron off, then rub an old paraffin candle end on the sole plate. The melting wax dissolved any sticky, ironed-on goo, and the excess wax was ironed off onto an old rag. Nowadays, you are probably better off with the commercial remedies. If you do resort to candle ends, do it CAREFULLY--hot wax is a BURN hazard. It is also a FIRE hazard as are old waxy rags--make those single use. And of course, with any remedy, home made or commercial, be sure to iron all the residue off onto rags.

GETTING THE CURL OUT (or at least taming it)

Stockinette curls. Perhaps the most annoying curl of all comes when a stockinette item is edged with a non-curling fabric--an edging which is SUPPOSED to stop the problem. Up flip the sweater hems, bands and cuffs, or down they curl, or maybe both. The one thing they don't do is lay flat.

A tangent on band flipping and curling

Typically, a garment pattern will call for a band of a non-curling fabric to be knitted onto a stockinette fabric.

The chain of logic behind non-curling stitch bands is this: the garment designer notices, correctly, that stockinette stitch curls like mad, but that garter stitch (seed stitch, ribbing etc.) does not curl or flip.

"Ah ha!" says the designer, "I will put a garter stitch band on this stockinette item I am designing, and then the stockinette fabric will be tamed, and the garment edge will not flip or curl."

Logical, yes. But still wrong.

See, garment edge itself will not curl up. However, the whole garment continues to curl, taking the "non curling edge" right along with it.

The fact that the bands are curling and flipping is due the stockinette fabric to which the non-curling stitch bands have been attached, rather than with the bands themselves.

Helpers in the fight against curling:

CHEMICALS, BLOCKING and STEAM IRONING

Chemicals, blocking and ironing are all actually very common knitwear treatments, albeit commercial knitwear. Think about it: don't you wonder why machine-made items of stockinette consent to lay flat, while hand knits want to curl so badly? The answer is partially because machine-made knits are generally knit from finer yarn than handknits, and so the thinner yarn from which they are made can exert less curling force. However, that is not the whole answer.

Hand knitters faced with curling or flipping can take a page from commercial knitting's playbook. For chemical treatments,

fabric relaxer is a good start.

Evidently the relaxer is essentially a wetter, which lets moisture into the fabric fibers, causing them to swell a bit, and de-kink.

Once damped with fabric relaxer, the item can be further wetted with a spray bottle of water, or even a quick trip to the sink for a brief soak, and this treatment can be followed by wet-blocking or steam blocking.

As far as mechanical processes, it is not just industrial knits which are stretched. Hand production knitters of the past have traditionally employed extreme blocking. Those picturesque

sweater forms (wooly stretching boards) in the old photos of the Shetland Islands had a very serious purpose, and couture knitting also

employs these techniques. Of course, extreme blocking like this is not only going to tame curling and flipping, but it is going to make the fabric grow. Commercial knitwear factors this in, but knitting purposely small followed by serious stretching isn't part of the program for most hand knitters--lace shawls being the exception.

And, this is where the steam iron comes in. It is the most mighty weapon against curling and all the other tricks hand knitting gets up to.

Now, a steam iron in the hand of a knitter is capable of producing three things:

- steam,

- heat, and

- pressure.

Each of these factors has the capacity to alter hand knit fabric, sometimes fatally, so the first rule of using the steam iron on your woollies is BE CAREFUL and amp up the power gradually.

STEAM

On wool and acrylic, the steam has as nearly as much effect as the pressing, so be sure that the STEAM setting on your iron is set on "high" right from the start. It may be that steam with hardly any pressure at all will do the trick,

as it does on kinked yarn .This is called steam blocking, and if it works, you're all set. In other words, on acrylic and wool, the ideal is to start with a steaming, billowing iron held just above the fabric, and only if this does not work, would you next progress to light dabs, and only then to pressure.

If your item is silk, bamboo, cotton--anything but acrylic or wool--do NOT start with billowing steam. Instead, start with the absolutely lowest steam AND the lowest heat AND the least pressure. Increase the steam in the same manner as you increase the heat and the pressure: in tiny increments.

Once your garment is nice and steamy, spread and smooth it with your hands (careful of the hot fabric though!) If needed, keep steaming and spreading, steaming and smoothing until the garment looks the way you want and the bands lie flat--or flatter, at any rate. Then, let it dry in the smoothed and stretched position. The dry time for steaming is far less than for wet blocking, but it still does need some time.

HEAT

Heat is a powerful tool on fabrics. Most obviously, a too-high heat can burn your precious hand knits. Even at non-burning temperatures, Heat can "set" woolen fibers--kink them permanently. It can melt acrylics, and can change the very composition of these and other fibers. Therefore, be careful. If the garment is woolen, be careful of scorching--maybe use a

pressing cloth or

flour sack towel between the garment and the iron. If your item is acrylic (or another synthetic) use the cloth or towel PLUS be careful of melting--increase the heat by VERY slow degrees, and realize that non-wool, non-acrylic fibers are generally even less resistant to heat. SLOW is the watchword for increasing the heat.

PRESSURE

All knitting three-dimensional, so ironing has the capability if flattening it. When working on stockinette garment with garter or ribbed bands, remember that the bands have no tendency to flip. It is the stockinette which presents the problem. Luckily, the stockinette is far flatter than the garter stitch or ribbing, and less likely to show the effects of pressure. If you get as far as actually ironing the fabric, keep the iron dabbing lightly on the stockinette part of the fabric only, and the greater the pressure you are exerting, the more careful you must be of this.

COMBINATION OF ELEMENTS

For wool and acrylic, start with a fully steaming iron. Progress in pressure and heat carefully. For other fabrics, start with the bare minimum of steam, and progress in steam pressure and heat carefully, increasing each factor, one at a time, in tiny steps.

As to the interplay of heat and steam, most irons will give steam on the wool setting, but there are two higher settings, usually: cotton and linen. For hand knits, I can't think when you'd ever get above the wool setting for actually touching the fabric with the iron, even with a thick ironing cloth. However, you might get into the higher settings if you want to generate a lot of steam. So, if you're on the cotton or linen setting for the steam effect, turn the iron back down to wool setting and let a cool a little minute if you're going to actually touch the iron to the fabric.

Steam ironing is a big gun--it certainly has the power to persuade curling stockinette to mend its ways, thus helping in the fight against flipping. But, there's a trade-off. The price for actually ironing at high heat, pressure and steam is a listless fabric.

I knew a production hand- and machine-knitter who HEAVILY ironed all her garments--and she made many, many garments over the years that I knew her. All those many garments did her bidding. They lay flat, yessiree, no question: never a curl, never a flip, no misbehavior at all, and the bands got up to no tricks. However, all those garments were oddly limp, with none of the spring normally associated with knit garments.

ALSO RELEVANT:

(

You have been reading TECHknitting on: "Steam iron your knitting.")

includes 7 illustrations. Click any illustration to enlarge

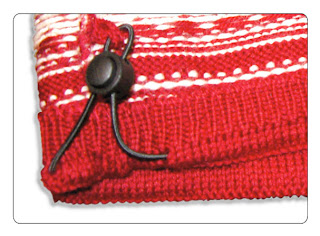

includes 7 illustrations. Click any illustration to enlarge As you can see, the scarf in the photo above is a stockinette stitch scarf with a garter stitch border all around. Yet, the scarf does not curl, and the borders do not flip, and here is why:

As you can see, the scarf in the photo above is a stockinette stitch scarf with a garter stitch border all around. Yet, the scarf does not curl, and the borders do not flip, and here is why: One more close-up for good measure:

One more close-up for good measure: